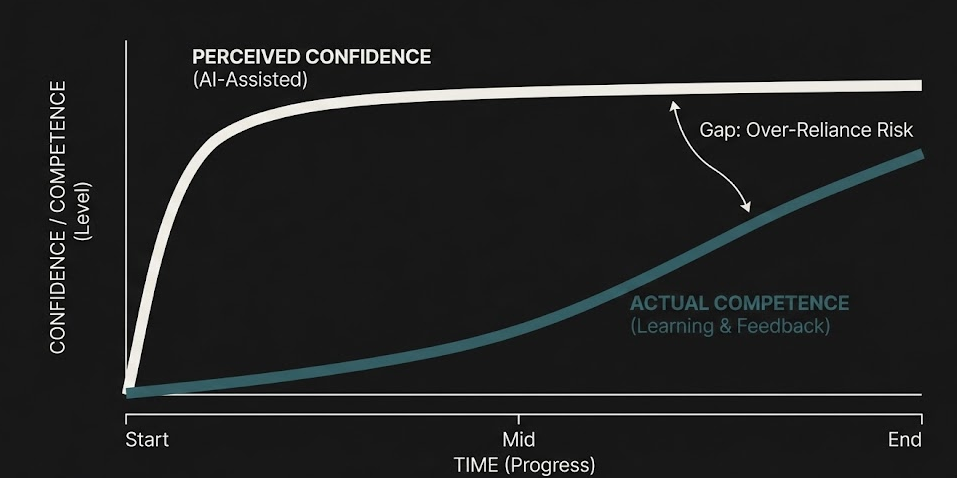

When Confidence Detaches From Competence

Conversational AI alters how confidence is earned - It allows assurance to grow without a matching increase in understanding.

The standard reassurance is that confidence has always been fragile. People have long overestimated their abilities, confused familiarity with mastery, and relied on borrowed authority. Conversational systems merely expose an old flaw. That response underplays the change. What is new is the speed and reliability with which confident performance can now be produced, independent of the user’s internal grasp of the task.

Confidence becomes performative

In most skilled domains, confidence used to lag behind competence. It was tempered by friction. One had to struggle through material, defend a claim in discussion, or withstand correction. Conversational systems remove much of that resistance. They deliver fluent explanations, plausible arguments, and well-structured outputs on demand. The user experiences success without the accompanying feedback that would normally recalibrate self-assessment.

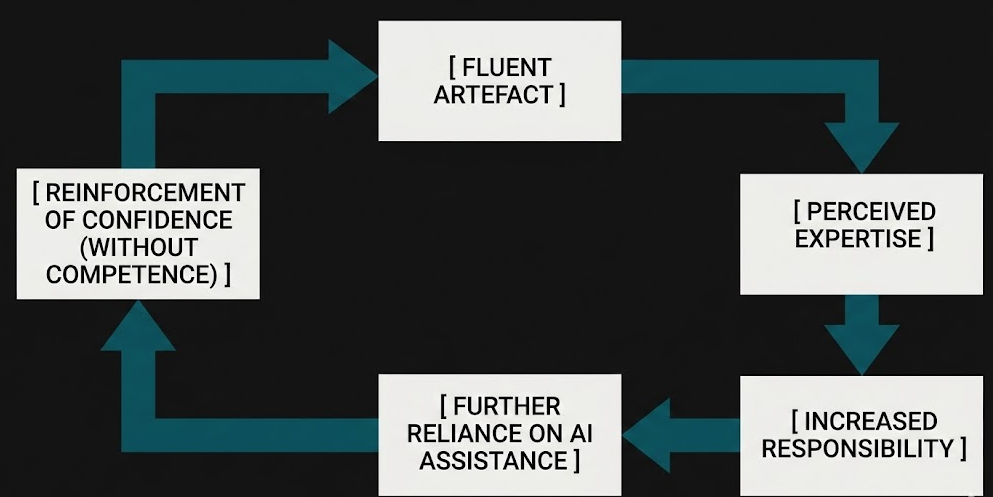

A single professional moment illustrates this shift. A lecturer unfamiliar with a specialist subfield asks a conversational system to help draft a short explanatory note for students. The result reads smoothly and uses the right terms. The lecturer feels reassured and proceeds to teach from it. When students ask probing questions, the lecturer struggles to extend or defend the explanation. The earlier confidence was anchored to the quality of the text, not to the depth of understanding behind it.

That mismatch is uncomfortable. It is also increasingly common.

Confidence is not just a feeling. It shapes behaviour. People who feel competent speak more, defer less, and take on higher-stakes tasks. When that confidence is scaffolded by fluent assistance rather than by internalised understanding, the calibration breaks. Errors are not recognised early because the subjective sense of readiness remains high.

This matters beyond individuals. In organisational settings, confidence travels with artefacts. A well-written report signals expertise regardless of how it was produced. Reviewers infer competence from tone and structure, especially when they lack the time or knowledge to interrogate substance. Once accepted, that signal feeds back into role allocation and trust. The author is seen as capable. They are given more responsibility. The loop tightens.

Figure 1 - Divergence between confidence and underlying competence

The educational consequences are subtle. Students who rely heavily on conversational systems can produce work that meets surface criteria while bypassing the cognitive effort that consolidates knowledge. They receive positive signals - grades, praise, progression - that would normally indicate learning. When asked later to reconstruct arguments or apply concepts in new contexts, performance collapses. The confidence remains, briefly, until reality intrudes.

This is not laziness -It is miscalibration.

Institutions often reinforce the problem inadvertently. Assessment regimes reward outputs rather than processes. Professional environments reward delivery rather than comprehension. In such contexts, fluent assistance fits neatly. It helps people meet expectations while masking the erosion of underlying skill.

There are limits to this effect. In domains with immediate, unforgiving feedback - physical skills, live performance, certain forms of technical debugging - miscalibration is corrected quickly. The danger concentrates where feedback is delayed or indirect, and where confidence itself functions as a gatekeeper to opportunity.

Figure 2 - Circulation of confidence through artefacts and roles

Calls for humility or restraint do little here. The system rewards confidence and punishes hesitation. Those who pause to verify appear slower and less decisive. Over time, environments drift toward favouring those who sound sure, not those who are careful.

Breaking this loop requires confronting an uncomfortable possibility. Confidence can no longer be treated as a reliable proxy for understanding. It must be re-earned through visible engagement with uncertainty, evidence, and limitation. That re-earning has costs. It slows work. It exposes ignorance. It resists the smoothness that conversational systems provide.

The alternative is to accept a widening gap between how capable people feel and what they can actually do.

That gap does not announce itself loudly - It reveals itself when it is too late to close quietly.