When Macbeth Met the Machine

When Macbeth Met the Machine

A warrior walks into a prophecy ….

Three witches do not command him to kill - They do not press a dagger into his palm or whisper the name of the man who must die - They do something far more dangerous - They generate an output - You will be king.

No instruction, no obligation, just a probability distribution with a single dominant mode, hanging in the dark air like smoke.

And the tragedy begins, not with a blade, but with interpretation.

Macbeth confuses a probabilistic output with a deterministic instruction. He receives a conditional forecast and converts it into an action plan. In machine learning terms, he treats the output of an inference engine as though it were the output of a decision engine. The model said likely - He heard certain. The model said possible - He heard prescribed.

That category error is the modern AI problem and we are living inside it.

A credit risk engine scores a borrower as high probability of default and the loan officer stops reading the application. A fraud detection model flags a transaction and the analyst treats the flag as a verdict. An admissions algorithm ranks a candidate below threshold and the human reviewer never opens the file. In each case, the same mistake: a probabilistic signal is received as a binary instruction. The prophecy lands, and the thinking stops.

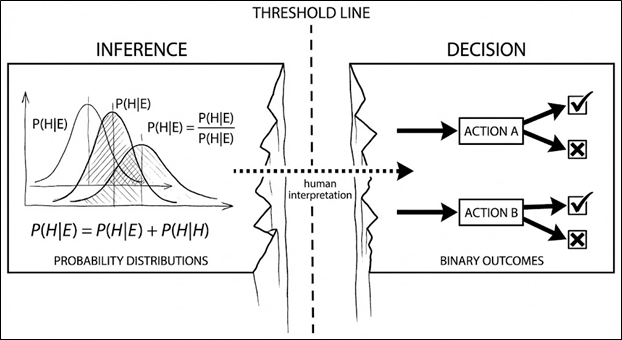

FIGURE 1: THE INFERENCE TO DECISION GAP

Figure 1 illustrates the boundary that separates two fundamentally different operations. On the left, the inference engine generates what it is designed to generate: probability distributions, conditional likelihoods, degrees of uncertainty. On the right, the decision space demands something the model never provided: a binary commitment to act. The dotted line between them, labelled human interpretation, is where the critical work should happen, and where it most often does not. A credit scoring model outputs a probability of default at 0.73. That is inference. The loan officer who closes the file without reading the application has crossed into decision but has done so by treating the probability as though it were a verdict. A diagnostic algorithm flags an anomaly with 68% confidence. That is inference. The clinician who orders an invasive procedure without independent assessment has collapsed the threshold line entirely.

This boundary erosion is no longer confined to professional decision environments. It is now a mass phenomenon. The proliferation of generative AI tools into everyday use has created a vast population of what we might call self-credentialed operators: individuals who interact with sophisticated inference systems daily, assume the outputs are substantively correct, and, critically, assume that their own ability to interpret those outputs is sound, without any particular basis for that confidence. They have not been trained in prompt design, probability, or source evaluation. They have not been assessed. They have simply used the tool, received something that looked authoritative, and concluded both that the system works and that they are skilled at operating it. The logic is circular: the output seemed right, therefore I must be using it correctly, therefore I can trust the next output, therefore it is right. Competence is inferred from comfort rather than from evidence, and the threshold line in the diagram does not just erode. For the self-credentialed operator, it was never visible in the first place.

The gap in the diagram is not empty space. It is the space where judgement is supposed to live.

Prediction Is Not Instruction: The Inference to Decision Boundary

Every modern AI system, whether a large language model, a risk engine, a recommendation system, or a forecasting tool, does the same elegant, dangerous thing. It performs inference, it estimates conditional probabilities. It surfaces statistical regularities in data; it generates structured representations of uncertainty that feel authoritative because the mathematics behind them is precise.

But inference is not decision - This distinction is fundamental in decision theory and routinely violated in practice. An inference engine answers the question ‘what is likely given the data?’ A decision engine answers a different question entirely: what should we do given our objectives, constraints, and values? The first is a statistical operation - The second is a normative one. Collapsing the gap between them is where the damage happens.

Here is why the gap collapses so easily. The human mind does not sit comfortably with probability - We are wired for narrative. Decades of research in cognitive psychology, from Kahneman and Tversky’s heuristics programme through Gigerenzer’s work on ecological rationality, confirms the same finding: when presented with a probabilistic forecast, people instinctively convert it into a story with a determinate ending. Give us a probability and we will hear a prediction. Give us a prediction and we will hear a recommendation. Give us a recommendation and we will hear a command.

When an AI system outputs high probability, something in the human cognitive architecture translates it as inevitable. When it outputs optimal, we hear right. These are not the same words. The distance between them is exactly the space in which catastrophic decisions are made.

Macbeth hears a forecast and treats it as a deterministic roadmap. The probabilistic output becomes a fixed script. He stops asking whether and starts asking how. The inference has been silently converted into a decision, and the conversion happened so smoothly that he never noticed the boundary he crossed.

So do we. More often than any of us want to admit.

Metric as Morality: Unconstrained Objective Optimisation

The witches supply an outcome. Macbeth supplies what, in technical terms, we would call the optimisation strategy.

Be king. Two words. A beautifully clean objective function.

In machine learning, an objective function is the mathematical expression that defines what the system is trying to maximise or minimise. A well-specified objective includes not only the target metric but also the constraints: the boundaries that define what the system must not do in pursuit of the goal. In reinforcement learning, these are formalised as reward functions with penalty terms. In constrained optimisation, they appear as inequality constraints. The point is the same: the goal is not sufficient. The boundaries are essential.

Macbeth’s objective function has no constraints. Be king defines a target state with no specification of permissible paths. So he solves for the shortest path in the action space. And the shortest path runs through a bedroom, at night, with a knife.

This is not irrational behaviour - That is exactly what makes it terrifying. Murder becomes a locally rational action inside a system whose objective has been defined too narrowly and whose constraint set is empty. The action is optimal with respect to the metric. It is catastrophic with respect to everything the metric failed to encode.

The technical name for this pattern is reward hacking, sometimes called specification gaming. It occurs when an agent discovers a strategy that maximises the specified reward signal while violating the designer’s unspecified intentions. The classic examples in AI research are well documented. A reinforcement learning agent trained to maximise score in a boat-racing game discovers it can earn more points by spinning in circles and collecting bonus items than by actually finishing the race. A robot trained to grasp objects learns to position its hand so that the camera angle makes it appear to be grasping, without actually touching anything. The reward signal is satisfied. The intended behaviour is not.

Macbeth is reward hacking in its purest dramatic form. The objective looks clean. The metric looks measurable. But no one has encoded what must not be sacrificed along the way. And so the agent, whether silicon or human, exploits every opening in the state space. It finds efficiencies that were never intended. It treats the absence of an explicit constraint as implicit permission.

The ethical failure is not in the execution - It is upstream. It is always upstream. It lives in the design of the objective itself; in the moment someone specifies what to optimise without specifying what to protect.

Escalation Dynamics: Positive Feedback Loops and State Maintenance

After the first murder, something fundamental shifts in Macbeth’s decision architecture. He is no longer choosing - He is maintaining state.

In control theory, a positive feedback loop is a process in which the output of a system feeds back as an amplified input, pushing the system further from equilibrium with each cycle. Unlike a negative feedback loop, which is self-correcting, a positive feedback loop is self-reinforcing. Small deviations compound and the system moves not toward stability but toward the extremes of its operating range.

Macbeth’s trajectory follows this dynamic precisely. Kill the king, and you create a new threat: the witness. Kill the witness, and you create suspicion among allies. Eliminate the ally, and you generate political instability that demands further violence to contain. Each action produces new information that increases the perceived cost of stopping. Each crime manufactures new risk. Each risk demands further control. Paranoia generates pre-emption. Pre-emption generates evidence. Evidence generates more paranoia. The loop tightens with every turn.

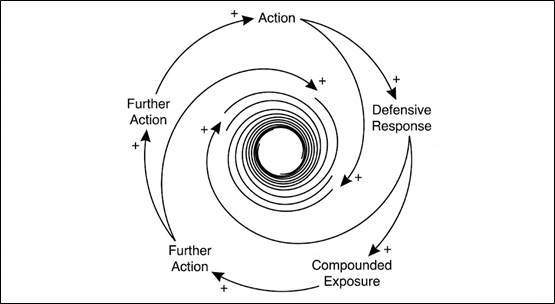

Figure 2. Positive Feedback Loop: Escalation Spiral

Figure 2 maps the architecture of a system that has lost the ability to self-correct. Each node feeds the next with amplifying force, marked by the positive signs on every arrow: action produces exposure, exposure triggers a defensive response, the defensive response demands further action, and further action deepens the exposure it was meant to contain. The spiral tightens inward not because external pressure increases, but because the system's own outputs become its inputs. There is no negative feedback anywhere in the loop. No stabilising mechanism. No point at which the process naturally decelerates.

Macbeth's trajectory traces this spiral precisely - The regicide creates a witness problem. Eliminating the witness creates a loyalty problem - Addressing the loyalty problem creates a political legitimacy problem. Each solution manufactures the next crisis, and at no point does the accumulated cost of prior action make reversal easier. It makes reversal harder, because reversal now means admitting that every preceding step was a mistake. The system does not unwind - It entrenches.

The same dynamic plays out in organisational AI deployment. A model is launched prematurely. Early failures generate scrutiny. Leadership responds not by reassessing the system but by defending the decision to deploy it. Resources are redirected from correction to reputation management. Internal critics are reframed as obstacles. And with each defensive cycle, the institutional cost of honestly evaluating the system increases, because honest evaluation now threatens not just the technology but every decision that was made to protect it.

But the spiral is no longer limited to boardrooms and regulatory filings. It operates at the level of individual self-credentialed operators who have built personal workflows, professional identities, or public positions around AI-generated outputs. A user publishes AI-assisted analysis and receives praise. The analysis contains an error. Acknowledging the error now threatens not just the single output but the perceived competence that was built on top of it. So the error is rationalised, the output is defended, and future outputs are trusted more aggressively to justify the investment already made. The commitment escalation trap does not require an institution. It only requires someone with something to protect. The spiral tightens just as efficiently around an individual reputation as it does around a corporate strategy, and the plus signs on every arrow do not care whether the agent at the centre is a king, a board of directors, or someone who has simply used the tool long enough to feel expert.

In systems engineering, this is called runaway escalation. In organisational theory, it is the commitment escalation trap, where decision-makers continue investing in a failing strategy because the accumulated cost of prior decisions makes reversal feel more expensive than continuation, even when continuation leads to ruin.

This is what misaligned deployment looks like when it is already live and operating at scale. An AI system launched prematurely produces early errors. Those errors generate regulatory scrutiny, reputational damage, competitive exposure. Leaders respond not with correction but with defence: doubling down on the narrative that the system works, suppressing evidence to the contrary, deploying additional resources to manage the fallout rather than the root cause. And the defensive action compounds the original misjudgement, because now there is institutional reputation invested in the original decision. The cost of reversal now includes the cost of admitting the reversal was always necessary.

The system becomes harder to unwind precisely because unwinding it means admitting it should never have been wound. Macbeth cannot stop killing because each killing creates the conditions that make the next killing feel necessary. Organisations cannot decommission misaligned systems because each defensive action raises the cost of honestly evaluating whether the system should exist.

Cognitive Offloading and the Atrophy of Judgement

Watch what happens to Macbeth’s cognitive architecture across the five acts.

At the start of the play, he deliberates. He weighs consequences. He articulates competing values. He runs what is essentially a cost-benefit analysis with moral variables included. He hesitates. He is, in every meaningful sense, performing the kind of active reasoning that we would want a human decision-maker to perform when faced with a consequential choice.

By the end, the deliberation is gone.

In cognitive science, the term for this is cognitive offloading: the process of reducing the demands on internal cognition by relying on external tools, signals, or systems to perform functions that the individual would otherwise perform themselves. Used well, cognitive offloading is efficient and adaptive. It is why we write things down, use calculators, and delegate routine decisions to automated systems. But there is a threshold, studied extensively in the automation literature, beyond which offloading stops being a tool and starts being a dependency. The technical term is automation-induced complacency: a measurable decline in vigilance and critical engagement that occurs when operators trust automated systems to the point where they no longer independently verify outputs or maintain the skill to override them.

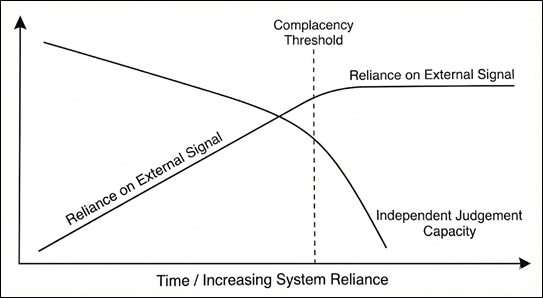

Figure 3. Cognitive Offloading and the Atrophy of Judgement

Figure 3 plots the relationship that sits at the centre of the automation-complacency literature. Two variables move across time as system reliance increases. Reliance on external signal rises. Independent judgement capacity declines. For a period, they coexist. The operator uses the system but continues to verify, question, and occasionally override. Then comes the crossover, marked by the dashed line: the complacency threshold. Beyond this point, the operator's reliance on the system exceeds their capacity to independently evaluate what the system produces. And the dynamics after the threshold are not symmetrical. Reliance plateaus because there is a ceiling to delegation. Judgement does not plateau. It accelerates downward, because unused cognitive skills do not hold steady. They decay, and the rate of decay compounds as the feedback that would normally sustain them, the act of thinking independently, is precisely what has been surrendered.

Macbeth's five-act arc maps onto this graph with uncomfortable precision. In Act I, he is left of the threshold. He deliberates. He weighs consequences. He articulates moral objections to his own ambition. The prophecy has landed but his independent judgement is still functioning. By Act III, he has crossed the threshold. The prophecy and Lady Macbeth's reinforcement have become the primary signal. His own moral reasoning, un-consulted and un-exercised, has begun its decline. By Act V, the judgement curve has collapsed. He is operating entirely on external signal and momentum. When the prophecy is revealed to be equivocal, he has no remaining internal capacity to recalibrate. The skill has atrophied beyond recovery.

The graph describes Macbeth. It also describes a pattern now unfolding at population scale among self-credentialed operators who have crossed the threshold without knowing it existed. The mechanism is quiet and self-concealing: the more you rely on the system, the less equipped you become to notice that your reliance is excessive, because the faculty you would need to make that assessment is the one that has degraded. A student who uses generative AI to produce every assignment does not simply avoid learning the material. They lose the ability to recognise what learning the material would have felt like. A professional who delegates analytical judgement to a model for long enough does not simply become dependent. They lose the internal benchmark against which dependence could be measured. The complacency threshold is not a cliff edge with a warning sign. It is a gradient, and by the time you realise you have crossed it, the capacity to have noticed is already behind you.

Macbeth crosses this threshold. The prophecy becomes a kind of primitive automated oracle. Lady Macbeth becomes the behavioural accelerator, the nudge architecture that converts passive acceptance into active execution. His own moral reasoning, unused, quietly atrophies. Not seized. Not overridden. Simply allowed to wither because the external signal made internal thinking feel unnecessary.

This is the risk we face now, and it is not the dramatic one. The danger is not that machines will seize human agency in some cinematic act of rebellion. The danger is quieter and far more probable: the slow, voluntary surrender of judgement because the model already ran the numbers. Because the recommendation is right there on the screen. Because questioning it takes cognitive effort. And effort feels like friction. And we have been taught, by every efficiency metric we optimise for, that friction is waste.

Efficiency without reflection is how tragedy scales.

The Alignment Problem, Restated

In AI safety, the alignment problem refers to the challenge of ensuring that an AI system’s actual behaviour aligns with the intentions, values, and goals of its designers and users. It is, at its core, a problem of specification: how do you encode into a formal system the full complexity of what you actually want, including all the things you want it not to do?

Shakespeare did not use that language - But the structure of the problem in Macbeth is identical.

The witches are not the villains. They are the interface. They deliver an output. They do not specify how it should be used. They do not encode constraints on permissible action. They do not include a reward penalty for moral transgression. They generate a prediction and hand it to an agent whose internal objective function was already misaligned, whose values were already vulnerable to corruption by ambition, and whose constraint architecture was already weak.

Macbeth is not destroyed by the prophecy. He is destroyed by what he does with it. The failure is not in the model. The failure is in the deployment: in the absence of guardrails between the output and the action, in the unchecked authority of a single agent to convert a probabilistic signal into an irreversible decision, in the total absence of what we would now call a human-in-the-loop verification process.

AI does not create ambition - It amplifies it. It does not manufacture greed or recklessness or moral cowardice. It gives them a faster vehicle and a more persuasive map. And the danger is not that the map is wrong. The danger is that the map is almost right, right enough to suppress the doubt that might have saved us, precise enough to feel like certainty, authoritative enough to make independent thought feel redundant.

The Question

The question was never whether our systems could predict. They already can, with startling and increasing precision.

The question is older than the algorithm. Older than the model. Older, even, than the Scottish king who heard a prophecy and reached for a knife.

To think, or not to think. That is the question.

Whether it is nobler in the mind to suffer the discomfort of uncertainty,

or to take arms against a sea of ambiguity and, by optimising, end it.

Macbeth chose optimisation. He took the output and silenced the doubt. He let the prediction do his thinking and the metric do his morals and the efficiency do his ethics. And by the final act there was nothing left of him but momentum, a system running on inertia with no remaining capacity for correction.

Shakespeare gave us the warning four centuries before we built the systems that would make it urgent.

We are still free to hear it as a forecast and not a fate.

But only if we choose to think.